The views expressed on today’s program are those of the speakers and are not the views of Today’s Workplace, the speaker’s firms or clients, and are not intended to provide legal advice.

Summary:

In January of 2020, a family from Wuhan traveling to Thailand would become the first case outside of China, since the first alert of the virus in December of 2019, which would kick start the spread of the novel coronavirus known to us now as COVID-19. It very quickly became a global pandemic due to the rapid rate at which it spreads to its victims. Counties had to shut down to curb the spread of the virus and flatten the curve. This has drastically impacted the everyday lives of individuals around the world who are now forced to lock themselves in their home in an attempt to promote social distancing.

Many people have felt the effects of this pandemic, whether it is from being directly infected by the virus, or indirectly affected through the loss of employment and financial security, or the mental strain and the effect it has on one’s health as the crisis continues.

Since this is a relatively new strain of the virus; scientists are still trying to figure out how it works and how to create a vaccine to counteract its effect. As a result, there has been some confusion or common misconceptions about how one should protect themselves, how the virus can spread and who is really susceptible.

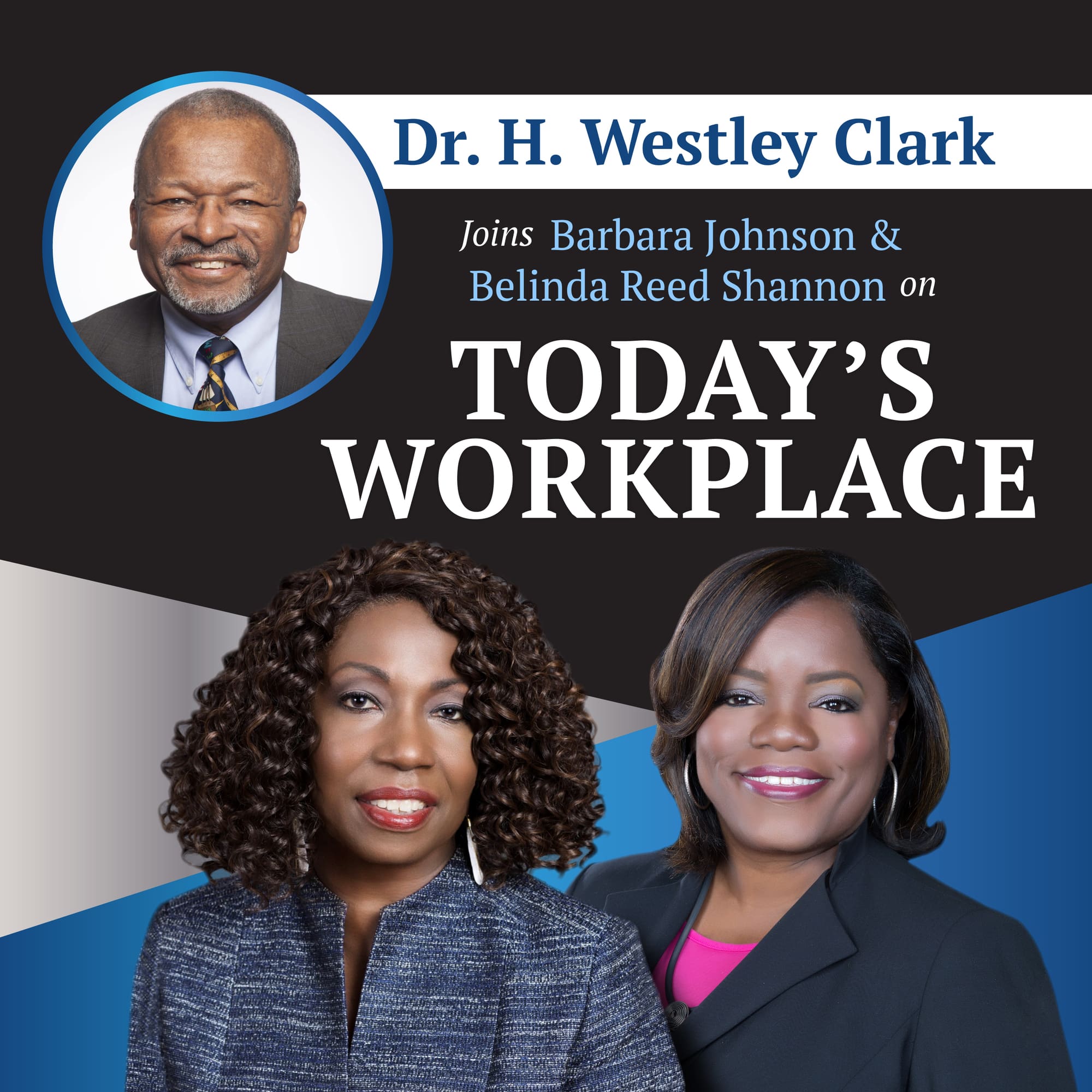

Joining us today is Dr. H. Wesley Clark. He is the Dean’s executive professor at Santa Clara university. He has a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Wayne State University and a medical degree from the University of Michigan School of Medicine, he also has a master’s in public health that he obtained from the University of Michigan School of Public Health. In addition to this, he has a law degree from Harvard University. H. Westley Clark, MD, JD, MPH is currently the Dean’s Executive Professor of Public Health at Santa Clara University in Santa Clara California.

He contributed to the US Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Health as a Section Editor for Treatment. He is a member of the National Advisory Council of NIDA. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the non-profit Felton Institute, He is also on the Board of Directors of the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation.

Dr. Clark received a B.A. in Chemistry from Wayne State University; he holds a MD and a MPH from the University of Michigan; He obtained his Juris Doctorate from Harvard University Law School. Dr. Clark received his board certification from the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology in Psychiatry. Dr. Clark is licensed to practice medicine in California, Maryland, Massachusetts and Michigan. He is also a member of the Washington, D.C., Bar.

Outline

25s Meet Belinda Reed Shannon

1m 20s Meet Barbara Jhonson

2m 28s Meet Dr. Clark

9m 50s What is COVID 19

8m 05s How did scientist know about the disease

m 30s What are the symptoms and the progression of the disease

11m 34s What was the response to the disease

14m 52s Who does COVID 19 affect

19m 51s How do we slow down the spread of the disease?

29m 37s What are the types of testing that’s available.

35m 32s is the US winning the war against this virus? Are we losing?

Narrator: Welcome to today’s workplace. The podcast created to keep employers current on the latest employment law trends while providing proactive solutions to the everyday issues arising in today’s rapidly changing workplace. Is your business prepared for today’s workplace? Let’s find out with your hosts, Barbara Johnson and Belinda Reed Shannon.

Belinda Reed Shannon: So many people in this country have been severely impacted because of COVID-19 and many of us have been dealing with working from home for more than four months because of the virus. Yet a lot of misinformation abounds, and it’s caused an unprecedented disruption to society and business globally. Just as we thought we were ready to open things up and start returning, to work from home to the workplace. There have been tremendous spikes in some areas of the country. Before we examine the specific impact of COVID-19 on the workplace we want to have a way to put it all in perspective and understand what is this really about? And so today we have a very special guest who’s going to provide us with a lot of information and a lot of perspective on what we know today as COVID-19. So, Barbara, why don’t you introduce our very special guests today?

Barbara Johnson: Thank you so much, Belinda. We are so fortunate today, to have with us, Dr. H. Wesley Clark. He’s the Dean’s executive professor at Santa Clara University and Dr. Clark as I said has just the perfect background because, not only does he have a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Wayne state university and a medical degree from the University of Michigan school of medicine, he also has a master’s in public health that he obtained from the University of Michigan school of public health and on top of that, he has a law degree from Harvard University. So, as I said, the perfect person to talk with us today, as we explore some of the scientific issues and public health issues around COVID-19.

Belinda Reed Shannon: I agree, Barbara, that sounds like a perfect background for this discussion. Hello, Dr. Clark.

Dr. Clark: Hello. Belinda.

Belinda Reed Shannon: Hi

Dr. Clark: How are you doing?

Belinda Reed Shannon: I’m doing great. I’m doing great. I think the best way for us to get started is for you to explain for those of us who are the nonscientists in our listening audience, why don’t you tell us what exactly is COVID-19?

Dr. Clark: Well COVID-19 is the name of the disease caused by a virus called SARS-CoV-2. COVID-19 was so named because it was first reported in 2019 and the name, was assigned to it by the World Health Organization and is a member of what is called the Coronavirus family and as a result, it is the SARS component which is Severe Acute Respiratory SynDr.ome and it’s a COVID-19 second COVID.

Belinda Reed Shannon: So, when we were first made aware of it, what was the reaction in the scientific community

Dr. Clark: While we weren’t made aware of it until December of 2019, when China alerted the WHO on a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown origin, this was in Wuhan China and then WHO, by January realized that we were dealing with this new virus or novel virus of the Coronavirus family and it was labelled, as I mentioned. So then in January of 2020, we had the first confirmed case of COVID-19 outside of China. It happened in Thailand and it was to a traveller who had visited China. By February, We had a confirmed case outside of China, in the Philippines, of a Chinese man from Wuhan and then, of course, we’ve continued to have cases in multiple countries around the world and February 14th, Egypt reported its first case and then we’ve had cases reported in Iran and Italy and then, of course, just about every country in the world.

Barbara Johnson: So, this is something that, you know, immediately was recognized as having a global impact and not just any one country?

Dr. Clark: Well, very quickly we became aware of the global impact by being able to track the presentation of the virus in different countries and so by March, the WHO had labelled this a pandemic mid-March and by a pandemic, I mean, this was a disease that was occurring in multiple countries and needed to be viewed in that context, because you also had to step up your assessment of people who presented in the emergency rooms for various reasons associated with this.

Belinda Reed Shannon: Did, at that time, did the World Health Organization have any idea how fast, this was spreading? So, they knew it was present in global communities everywhere, but did they have any idea how rapidly it was spreading within any one area?

Dr. Clark: Well, certainly, given the historical experiences with these respiratory infections, they became aware by mid-January that this was exactly happening as you pointed out- as I pointed out, people who have been in Wuhan had travelled to other places, wound up symptomatic. So, in January of 2019, WHO declared the outbreak had global public health emergency because, by that time, more than 9,000 cases were reported worldwide, including 13 countries outside of China. So, and then February 2nd, the first recorded death outside of China was reported as admitted in the Philippines. So, you’ve had multiple cases, multiple countries, and then people were reported dying outside of China. So yeah, I think WHO was very much aware but remember, late December, and so by, you know, essentially 30 days later, that gives you a sense of how rapid this and how infectious this disease was, or is actually.

Barbara Johnson: At what point did we officially have a pandemic and tell us what is a pandemic?

Dr. Clark: The difference between a pandemic and an epidemic is not clear. It’s a little vague, generally, an epidemic, which also doesn’t have a precise definition is when you’ve got multiple jurisdictions and a lot of people who are affected by a condition and historically it’s been an infectious disease, but we’ve heard the phrase epidemic applied to opioid overdose. We’ve heard that phrase applied to other circumstances. A pandemic, of course, would suggest a more global presentation, multiple countries and as well as many people in multiple countries. So, the key issue is, it’s happening in a lot of places to a lot of people.

Belinda Reed Shannon: But let’s talk about how COVID-19 affects people. What are the symptoms and has our understanding of the symptoms evolved over time?

Dr. Clark: and that’s, I’m glad you raised that question because again, you’ve got a rapidly evolving situation where first of all, we have no prior experience. The medical community, the epidemiological community, had no prior experience with this particular virus. It is called a novel Coronavirus, for that reason, the word novel meant that it had not happened in human beings before. So, the symptoms that appear two, fourteen days, after exposure to the virus include fever, chills, cough, shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, fatigue, muscle or body aches, headaches, loss of taste, of smell, sore throat, congestion or runny nose, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The sort of classical symptoms seen in emergency rooms would be trouble breathing or persistent pain in the chest and some sense of confusion, inability to stay awake or get to sleep and then bluish lips, showing some sense of oxygen, low oxygen in a person’s blood.

Barbara Johnson: And what is the progression of the disease? I mean, we know that it’s a disease that actually can kill you, but how does it progress?

Dr. Clark: again, most people just have the symptoms that I talked about in terms of the fever, the headache, the shortness of breath and they get better. So roughly 80 to 85% of people have symptoms that troubled them, but they get better. In fact, that’s part of the problem, because most people treat it like the regular flu that many of us have had and have treated symptomatically, maybe with a decongestant, maybe with an analgesic like Tylenol or an aspirin, but as it progresses, you start getting the increased difficulty with breathing and as I mentioned, sort of physical science, like a blue lips, or until you wind up going to the emergency room because you can’t breathe and then it gets, it either gets better or worse, but mostly the respiratory problems. Now the disease can manifest itself in a minority of people, at a full range of things, cause it can affect multiple organ systems and that’s something that we have to keep in mind. It isn’t just the pulmonary issues that you can have multiple organ systems involved, your heart well as your lung and other organs. So, when you ask, how about disease progression? You want to look at the full range of other clinical presentations?

Barbara Johnson: Oh, I was just going to ask. So, once we identified this as being a pandemic, tell us a little bit more about how the centers for disease control here in the United States and the World Health Organization, how did they respond? Start working together and start really defining how we should, as a society respond.

Dr. Clark: Historically, the CDC has worked with WHO and in fact, CDC often shared staff with WHO and in the past, the United States had an office in China that would have recorded these kinds of things. But apparently that was changed for reasons that are not clear to me, but as a result, there was a little delay. So nevertheless, WHO did report to the federal government, through the CDC. The CDC is tasked with being a recipient of this kind of information and it works with the respective States in the United States. So as well, because each state has its own health department, we don’t have a federal system of public health per se. Each state, each government, is responsible for public health within that jurisdiction. So, you have slightly different approaches to public health in each state. Nevertheless, CDC does use its platform to coordinate information with health officials and both States and counties. Remember in some jurisdictions, counties play a major role in terms of deciding what goes on in public health, depends on how large that particular county is. County health departments and state health departments all work closely with the CDC to make sure that adequate information is available and that something that’s happening in New York, that might harbinger something that’s going to happen in California, that information is shared, and you need a central clearinghouse for that information. Remember, in the modern environment, people travel all the time, airplanes, they are moving back and forth. So when you’re dealing with an infectious disease, you’re dealing with the disease that moves across boundaries and so while we don’t have a regulatory central authority at the federal level, because public health is a state-based responsibility, we do have the federal government sharing information, coordinating information and making sure that information is readily available to state authorities and County authorities and that is a role that CDC has. CDC also works at the federal level with the food and Dr.ug administration, particularly when you’re dealing with things like vaccines or diagnostic tests that have to be developed. So, in the case of SARS-CoV-2, we needed to have a diagnostic test. So, by mid-February, there were insufficient diagnostic tests available. The CDC did have an effort to develop diagnostic tests and that apparently was a little slow because it has its own laboratories and working with the FDA, it wasn’t until later in the month that they allowed state health departments to pursue diagnostic tests so that we could determine the presence and prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 as COVID-19 within our system.

Belinda Reed Shannon: Dr. Clark talk with us about COVID-19 and how it impacts people of different ages differently. There seems to be a lot of confusion about that out there, the idea that young people can’t get COVID-19, that older people get COVID-19 more, that chilDr.en don’t get COVID-19. Help us understand kind of what happens from an age perspective, with respect to the risk of contracting COVID-19

Dr. Clark: I think it’s safe to say that anybody can get COVID 19. Now, what your question suggests is that there is a difference in the clinical presentation and there a difference in the risk factors. So, you start off with, anybody can get it and the fiction that young people don’t get, is causing a major problem. So young people get it and the major problem is if you are an asymptomatic carrier or even if you’re symptomatic, but your symptoms aren’t that severe you’re walking around spreading the disease and that’s a problem. People who are immunocompromised, which tend to be older people, in some cases, people with other medical conditions, like diabetes, cancer, or hypertension, et cetera, what you wind up with is anybody along the age spectrum. So, we have the most severe impact, is with those who are very old and then it goes from very old, all the way down to very young, so chilDr.en can get it. Young adults, 18 to 29 tend to be more mobile and a lot of them believe that they can’t get it, they can and they do.

Belinda Reed Shannon: And they did

Dr. Clark: And they did. when you get confirmed cases, you find that in one study, the largest cohort of confirmed COVID-19 cases was in the age range of 50 to 64. So, they had, at the time, they had over 484,000, but the next largest cohort was in the 18 and 29 at 339. So there were fewer cases in the older population, in part, because it was people started to isolate but the death rate for people who are older, if you’re greater than age 85 or older, the death rate is something like 300 per thousand cases, versus if you’re 18 to 29, that death rate is like 1.1 deaths per a thousand cases, which points out that anybody can get it. Anybody can get sick, but older people tend to get sicker. Now, the notion of the asymptomatic carrier is that these young people who are often, depending on older people for resources may wind up, shall we say, compromising the health of those other people, they can’t work and therefore they can’t get support.

Belinda Reed Shannon: So you talked about, you know, anybody can get it from an age standpoint, but at this point, you know, five, six months into dealing with this, this COVID-19 at least in the United States, we’re seeing trends where certain racial or ethnic demographics are being impacted greater than other communities and can you just before we move from this topic, can you just share a little bit about why that is?

Dr. Clark: Well, we have to keep…

Belinda Reed Shannon: anybody can catch it

Dr. Clark: With a severe acute respiratory synDr.ome. So that means the next question is not only which age group, but the kinds of physical sensitivities you have. So, if you’ve got a situation where people are living more closely together, you’ve got a situation where people’s health is not as good as other people then what we wound up having is African Americans and Hispanics, as well as I’ve mentioned, senior citizens have a disproportionate impact. You also have the issue of nutrition, a food desert. So, you’ve got these systemic inequities in our economy and then finally, if you’re living in tenement houses or close proximity, then you’re more likely to get it. And then, then you’ve got people in the criminal justice system, which are disproportionately Hispanic and African American, in terms of dormitory facilities within the penal system, so they can get it. So, we do have some structural inequities in our economy and in our society, which then leaves people of color, poor people, at greater risk.

Barbara Johnson: Let’s see, thank you. So how do we stop or slow down the spread of the disease? And it’s interesting, as I think about it back in March, where everybody kind of turned on a dime and people started working from home, I personally have this view, okay, we’ll be here for a little bit and you know, then by June, July, everything’s good and we’re all gonna be back out there and we’ve heard a lot about flattening the curve. So, help us understand, first of all, what flattening the curve means and then secondly, what we’re saying in terms of our ability to stop or slow down the progression of this disease.

Dr. Clark: Well, the whole notion of flattening the curve is the notion that was developed from the experiences of 1918, from the Spanish flu, which was also a worldwide pandemic. The healthcare system gets overwhelmed by presentations, people get sick, that minority of people who really get sick, they show up in the emergency room. They require additional resources. They require the hospital, the clinic, to have what’s called personal protective equipment. So, you get this reallocation of resources. So, what you don’t want is a highly infectious disease to spread and increase the demand on those facilities. What they were trying to achieve with what’s sometimes called a lockdown, the stay at home orders, however you want to characterize it, is to reduce the risks that people have, getting exposed. You also had the issue of wearing the mask. Initially, there was some question about whether you should wear masks and then it became clear that you needed to wear a mask because that question surface, because we did not appreciate the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 we just, most recently within the past three or four weeks came to the conclusion that it was airborne. We didn’t know that at the time. So, the mask actually serves an additional purpose, but the key issue with this is, can you get citizens to cooperate? It all turns on the behavior of people. And as you pointed out, we all got tired of being locked down, shut out, shut down. They closed down our restaurants and we all wanted to go out and have a good meal. They closed down bars and we wanted to go out and have a Dr.ink. They closed down parks and we wanted to play soccer or football or tennis.

Belinda Reed Shannon: They just totally shut down the ability to socialize with anybody outside of your immediate family.

Dr. Clark: It did, indeed. I mean done so, you know, sort of hemmed and hawed and hemmed and hawed, then it became political but the undercurrents were, we needed people to come to grips with the fact that we needed to change our behavior, that an infectious disease that causes for a minority of people, some fairly profound conditions, can be devastating to the community and so after two months, the politicians relented, and hence we had the relaxation of these rules. Epidemiologists had predicted a wave. First wave, would go with subside because of the lockdown, the isolation order, to stay at home orders, worked. The disease would subside and then later, we would have another wave but that would come say in the fall or in the winter, unfortunately we’re not moving from the first wave to the second wave. It’s going great big way. So, because people started showing up, they made political statements, they had protests and in other communities that said, well, you know, we’re not political. We don’t care about the protest, but we’re going to the beach. Sun’s out, weather’s nice; gonna hang. And so, the combinations of protests, then we had other protests is happening because of social discord in our community. So, want to go back to work, tired of being in a home, It’s the political agenda, or I want to go swimming. We’ve found any number of reasons to go back to the status quo ante and that meant the disease would spread. So, some jurisdictions said you have to wear a mask. Other jurisdictions said you didn’t. Some jurisdictions said you should stay at home. Other jurisdictions say well we’re not sure. Most recently one state said that we were not going to allow the counties to impose masks on our communities. Nobody needs to wear a mask. Well, it’s an infectious disease that’s spread by people talking to each other and spitting when they talk or breathing when they talk.

Belinda Reed Shannon: or sneezing

Dr. Clark: or sneezing, or coughing. So, you know- I don’t know if those of you who are older will remember the peanuts cartoon, a kid called a Pig Pen.

Barbara Johnson: Wow.

Belinda Reed Shannon: This whirl

Dr. Clark: Well, you should think of a COVID as the same thing. When you walk into a room, you’ve got this little aura, infectious materials around you and the mask keeps that contained.

Barbara Johnson: So, the mask helps you keep your germs to yourself?

Dr. Clark: And yes, and it keeps you from being exposed to other people’s germs.

Barbara Johnson: Ok

Dr. Clark: So, you keep those to yourself and you’re not exposed to other people’s germs. So, it’s a twofer. Your stuff stays with you. Other people’s stuff stays with them and you are not exposed. And that is a very important thing. But if the attitude is, I can’t touch it, I can’t smell it, I can’t see it. It’s not there, then you’re unwilling to do that. You don’t want to wear a mask. You want to hang; you just don’t understand the importance of social distancing. Some places, like some of the big box stores, had things lined in supermarkets marked off six feet, people would just ignore the six feet.

Barbara Johnson: Yeah?

Dr. Clark: They had little things on the floor. This is 60 feet from that so

Barbara Johnson: Back up

Belinda Reed Shannon: That’s right.

Dr. Clark: So, the issue is if we can’t influence and convince people that, part of dealing with this condition, is personal responsibility. Then we’re going to have the ongoing problems and we’ve seen that in jurisdictions that previously relax their rules and then suddenly saw this uptick in people showing up in the emergency room and in the hospital. The ones who showed up, of course, were sicker and they required resources to be allocated. So, you now have hospitals in the States that did not have the same level of problems, overwhelmed. So, key thing is we need everyone to own this as a part of our obligations in our society, that wearing a mask is an inconvenience, but being definitely ill is more inconvenient.

Barbara Johnson: So, I heard you say, wearing a mask, social distancing, step back, sometimes staying, just staying at home. Any other ways we can, or that, we need to stop the spread of the disease. We should, of course, wash our hands. I don’t want to forget the 20 seconds washing hands thing so people have developed all sorts of timing things, wash your hands for 20 seconds at least. Wash both the front, the back. Wash it between your fingers and your fingernails. Again, an inconvenience, but you know, if you’ve ever been severely ill from anything, that inconveniences overshadowed by the price you’d pay from being so severely ill. And if you’ve got people in your family who are immunocompromised by any condition, then you don’t want to be responsible for impacting them and we’ve also got some young people who are discovering much to their chagrin and dismayed that they themselves were immunocompromised because you don’t always have to be severely ill to be immunocompromised. So, we’ve got 25-year olds and 30-year olds and 40-year olds who are dying from COVID-19 related conditions and it’s a real tragedy that we are trying to avoid. We need to avoid, and the only way we can avoid it is if we all hunker down and do what needs to be done, with that, you can go back to the store, you can go back to business, you can, but you’ve gotta be willing to do that. So, if you’re not willing to wipe down your surfaces, you’re not willing to wash your hands, you’re not willing to wear a mask. If you’re not willing to identify whether you have symptoms early in the process, then you do have a problem because you create a problem for the rest of us.

Barbara Johnson: You know, we hear a lot about testing for COVID-19, what is the importance of testing? And also, if you could just tell us about the types of testing that’s available.

Dr. Clark: First of all, we’ll start with the two types. There are two tests to determine whether you have what’s called an active infection. One is called a polymerase chain reaction or PCR tests. Another one is called the antigen test. The PCR test looks for pieces of the virus that causes COVID-19. It’s a test that they look in the nose and the throat and other areas in the respiratory tract to determine if the person has an active infection. That’s also true for the antigen. Nasal swab is taken by a healthcare provider and tested. Sometimes, if you’ve got a rapid test, it can be done while you wait. Other times it takes up to a week. The third test is what’s called the serology test or an antibody test. And this is from a blood sample that is taken and sent to a lab for testing. It tests whether you have a past infection. So, the act of the test, the PCR test with the antigen test, let you know whether you have an active infection or not. And if you test negative, it means that you don’t currently have that infection, but you really do need to take care of yourself by using the things that Belinda talked about, mask and washing, social distancing, et cetera, because just because you don’t have it, doesn’t mean you can’t get it and that is an important point. Whereas the antibody tests says you had it and that you now have antibodies as a result of having a problem with the, it’s not the test, the problem with having antibodies is for some diseases, If you’ve got antibodies, you’ve got immunity that lasts for a while. We’re not sure about the to the situation. There has been some indication that you may only have immunity that lasts for a couple of months if you have it, so we are still getting data. So, the key issue is if you have the antigen test, PCR tests with the antigen test, be careful. You don’t have it today. You might get it tomorrow, but if you have the antibody test, be careful, you had it. You’re obviously better because you’re walking around getting tested, but don’t get cavalier about it. So those are the two tests. Those are the three tests that are given. So, people develop, if you’re going to become symptomatic again, about 12 days from your exposure so be careful. Those are the tests. The significance of the testing is it’s often hard to get tests. I was just on a webinar earlier and there was an Island in Florida where everybody got tested. It’s a private Island, very rich people. They all met and then there was the gentleman who did the presentation also pointed out there was a jail and then it’s not too far away. Nobody could get tested. So, and then early in the testing process, we heard gee, Sam Smith from the NBA or John dokes from the hockey

Belinda Reed Shannon: Oh yeah.

Dr. Clark: They all got tested

Belinda Reed Shannon: Like immediately

Dr. Clark: Immediately but nobody else could get tested. So, the availability of testing is an issue and then some people have to wait a week. I had a friend who waited a whole week and still hadn’t heard about her tests. So those are things that you have to take into consideration in terms of the resources available to make the test available. The United States started more slowly than other countries like South Korea, China and so we had a situation where we didn’t test, we didn’t know and people just weren’t concerned. So now we’ve got more testing available. We really shouldn’t blame the testing; we should use the testing as a way of informing us of what to do in our homes and in our community. So, if you are negative from the PCR test, for the antigen test, stay safe by social distancing, hand-washing, wearing a mask. If you are positive, that means you have active infection. If you’re asymptomatic, you still want to isolate for two weeks approximately to make sure you don’t become symptomatic. If you’re an asymptomatic carrier, even though you don’t become symptomatic, that same two weeks applies because it means that you want to avoid exposing other people, young people, older people with your condition. It has had substantial impact; people can’t go to weddings; people can’t go to funerals. So, people are being inventive, zoom weddings, zoom funerals or postponed graduation ceremonies. People are figuring it out and other people are saying, what we worry and they go party. That was a case where some young people were having, shall we say, exposure parties. Let’s have a COVID-19 party and see who gets the infection first. You know..

Belinda Reed Shannon: Yeah

Dr. Clark: There we go

Belinda Reed Shannon: Yeah. So, let’s take a step back and look at this. So, we’ve got this disease, we’ve got evidence that it’s spreading very quickly and that it’s presenting itself globally. It has in effect, shut down economies across the world. Businesses can’t operate. Schools can’t operate. We’re being told how you can stop it from spreading. We’re also being told that there is some form of testing and they’re trying to find, I guess, a cure for it. So how long does this last? What should we expect moving forward? And just as a country, the US are we winning the war against this virus? Are we losing?

Dr. Clark: Fortunately, you get a jurisdiction by jurisdiction response. So, some States are doing very well, other states are not doing so well. Some states, people are cooperating in and that’s why they’re doing well, other States, people are saying, I’m tired of all of this social isolation and not being able to go to the bar and not being able to party. So, you’re not getting that cooperation. So, as you pointed out earlier, some states like Texas and Arizona and Florida seemed to be moving in the right direction and then boom, the party started to happen. So, people valued the economy over their public health and we recognize that there is this balancing act that you have to do, but the balancing act, the economy is preserved by people cooperating. If people are not going to cooperate. So, the only way I can go to a bar is to expose myself to everybody else, then that’s a problem. The other way I go to a restaurant is exposing myself to everybody else, that’s a problem and it’s having a substantial impact because from a workplace perspective, who’s responsible for those people. So those States that shut down and now that their hospitals are being taxed, they’ve had to step back and say, Oh, wait a minute. We thought this was about civil liberties. We thought this was about the constitution. It is really about an infectious disease, which is in any place I can find in the constitution or the bill of rights.

COVID-19 Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/index.htm

CDC-Print Resources:

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/communication/print-resources.html?Sort=Date%3A%3Adesc

CDC Workplaces and Businesses:

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/workplaces-businesses/index.html

Cleveland Clinic-COVID-19 Video:

The New York Times – The Coronavirus Outbreak:

Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center:

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/resource-center/COVID-19-Resources

National Institutes of Health

https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/whats-new/

NBC News

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/coronavirus

Washington Post

https://www.washingtonpost.com/coronavirus/?hp_top_nav_coronavirus